|

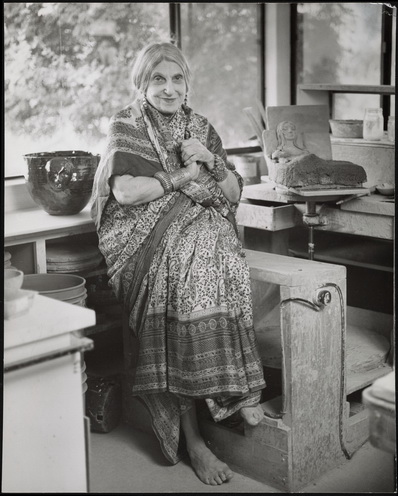

Beatrice Wood | |

| Birth Date: March 3, 1893 |

||

| Death Date: March 12, 1998 Artist Gallery |

||

| Beatrice Wood was born in 1893 in San Francisco to wealthy parents, moving to New York when she was five. In her 20s she renounced her family’s fortune, setting into motion a life of independence that was rare for women of her generation.

In 1912, Beatrice rejected plans for a coming-out party and announced that she wanted to be a painter. Her mother then arranged for her to study in Paris at the Academie Julian, but she found the education tediously academic. Instead, Wood turned her attention to the theatre, appearing on stage with the leading stars of the time. Her acting career was cut short by the outbreak of World War I and she returned to New York, joining the French National Repertory Theatre using the stage name Mademoiselle Patricia to hide her family name.

Through friends, Wood became acquainted with artist Marcel Duchamp and other members of the Dada movement, including the art collectors Walter and Louise Arensberg, whose apartment served as a nightly meeting place for artists and where important art movements such as Dada emerged. Wood began sketching and painting with Duchamp and artist Henri-Pierre Roché, forming the Society of Independent Artists which published “The Blind Man,” a seminal Dada journal.

Although a 1993 documentary later dubbed Wood the “Mama of Dada,” she is rarely listed among the movement’s pioneers. But in 1917, both she and Duchamp submitted works to the Society of Independent Artists’ first exhibition, which would double as Dada’s coming out. While Duchamp’s contribution to the show—a found urinal titled “Fountain” —would later be seen as an important moment in the history of modern art, it was Wood’s “Un peut (peu) d'eau dans du savon” that caused public uproar at the time. The painting showed a woman’s naked torso with a real piece of soap affixed “at a very tactical position,” Wood would later explain.

After her irreverent debut in the New York art scene, Wood relocated to Montreal then California, where she began making the shimmering ceramic vessels and satirical figurative sculptures that she’s become known for. Her career in ceramics started after a trip to Holland in the late 1920’s, where Wood purchased a set of baroque dessert plates with a shining luster glaze. Unable to find a matching teapot, she decided that she could simply make one and in 1933 enrolled in a ceramic course at Hollywood High School. She found that making ceramics was not as easy as she had thought, but she persevered and within a few years had her own small shop where she sold her work and gave demonstrations. “I never meant to become a potter,” Beatrice later said. “It happened very accidentally.”

In the late 1930s, Beatrice Wood studied ceramics with Glen Lukens, a leading artist and teacher. She learned a great deal from Lukens, and he served to prepare her for her most important mentors - Gertrud and Otto Natzler. Acclaimed for their refined sensibility and technical knowledge, the Natzlers took her on as a student, sharing their techniques and glaze secrets. While the Natzler’s sought control over their works through mastery of technique, Wood's were loose and unconventional by comparison, freely exploring form, glaze combinations and happenstance - exhibiting an embrace of artistic naiveté and the unexpected results of the kiln.

In 1947, Wood felt that her career was established enough to build a home and studio in Ojai, California. By this time her work had been included in museum exhibitions and she was receiving orders from major department stores including Neiman Marcus, Gumps, and Marshall Fields. Wood fell in easily with the community of artists and actors in Ojai. She began a lifelong friendship with ceramicists Vivika and Otto Heino, who helped her develop her throwing skills and shared techniques for working with luster glazes. Wood became established, teaching ceramics for the Happy Valley School (now called the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley) and operating her studio and showroom.

In the 1960s, Wood traveled to Japan and India, and amassed a large collection of folk art as well as the saris which she preferred to wear over western dress. India and its art also inspired her use of surface texture, color, and ornamentation, and she would visit the country a few more times.

In 1974, Wood was invited by her friend Rosalind Rajagopal to build a home and studio on the grounds of the Happy Valley Foundation. Wood lived on the 450-acre parcel of land in the upper Ojai Valley with the understanding that the home would be gifted to the Happy Valley Foundation upon her death.

The last twenty five years of Wood’s life were her most productive and prolific, and she became well-known for her vessels with luster glazes. She developed her own version of the unpredictable luster glaze technique, a process that embedded the metallic iridescence into the glaze itself, rather than painting it on. While she didn't invent the technique, she did create a unique palette in an extraordinary range of metallic pinks, golds, and greens. Though she became a ceramicist of note with her bowl and vessel forms, her sculptural work contributed a considerably different body of work to the field of contemporary art. These works, which she called her "sophisticated primitives,” reflected her love of folk art as well as the influence of Dadaism.

Wood was in her late eighties when her first book, “The Angel Who Wore Black Tights,” was published. A few years later, her autobiography, “I Shock Myself,” was published, followed by “Pinching Spaniards” and “33rd Wife of a Maharajah: A Love Affair in India.” Her relationship with Marcel Duchamp and Henri-Pierre Roché was said to have inspired the latter's book “Jules and Jim,” which was made into a celebrated French film by director François Truffaut.

Wood was also the subject of films, most notably “Beatrice Wood: The Mama of Dada,” created on the occasion of her 100th birthday. Toward the end of her life, Beatrice provided inspiration for the character of "Rose" in James Cameron's film “Titanic.”

Beatrice Wood passed away in 1998, at the age of 105. Ultimately, her genius was in the marriage of wide-ranging influences in her work. The spirit of Dadaism, impact of Modernism, embrace of Eastern philosophy, and influence of folk art were all combined in her ceramics. Her work reveals a mastery of form, combined with a preference for the naïveté of folk art. It is impossible to separate her life experiences from the work she created, as they were truly intertwined, and each piece represents her mastery of the art of life.

|

||