|

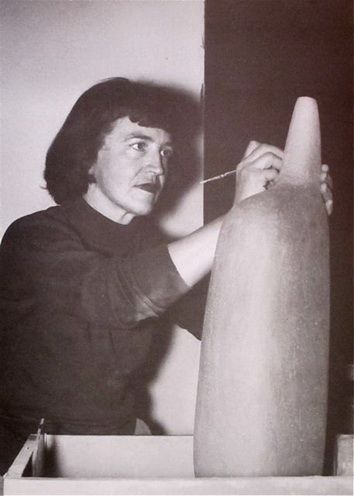

Leza McVey | |

| Birth Date: May 1, 1907 |

||

| Death Date: September 22, 1984 Artist Gallery |

||

| Some ceramics historians feel that Leza McVey was one of the most talented ceramicists of the 50s and 60s, but her work has been largely forgotten.

Leza McVey was one of the leaders in moving the traditional ceramic vessel form toward asymmetrical and freeform forms. Born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1907, McVey inherited her artistic inclinations from her mother, who had studied at the Cleveland School of Art. Leza herself would go on to become an innovative American ceramist who studied at her mom’s alma mater, the Cleveland Institute of Art (1927–1932) and at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center (1943–1944). In 1932, she married the sculptor William Mozart McVey, and from 1935 to 1947, she worked as a ceramist in Houston, Austin, and San Antonio. She contributed to her husband’s projects behind the scenes, as was common for married women artists at the time. William accepted a teaching position at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan in 1947, and there Leza met the Finnish artist Maija Grotell. She also became friends with the Japanese-American artist Toshiko Takaezu, who studied at the Cranbrook Academy from 1951 to 1954. Her studies with Maija Grotell at Cranbrook were an important turning point for McVey’s career—she continued to make vessels, but rather than throwing them on the wheel, she began to build them by hand, and in doing so eschewed the traditional emphasis on symmetry. In 1953, McVey returned to her native city of Cleveland and established her studio in the suburb of Pepper Pike, Ohio.

McVey was rebellious in her ceramics. Her work focused on form, not surface decoration, and her vessels were rarely utilitarian. She frequently made stoppers for her bottles that were abstract in nature and sometimes resembled human or animal heads. When she used patterns, they had plant or animal characteristics. Unlike her contemporaries, McVey disapproved of taking ideas and forms from previous cultures. She once stated in Ceramics Monthly that “To me it is more gratifying to fail miserably in trying to live in today’s world than to succeed knowingly imitating products of some distant, unfamiliar place or people.” Instead, she focused on vessels of abstracted zoomorphic forms (like cats or chickens) and freeform, organic vessels that were tied to the modern, Surrealist moment. On organic forms, she said, “A generation of artists raised in cities, removed from awareness of natural organic forms, is losing touch with the unities of nature.”

At the height of her career in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, Leza McVey was one of the best known American ceramists. She showed her work at the biggest craft exhibitions in Syracuse, Detroit, and Toledo. The original organic forms that she created won prizes and critical acclaim. Her decision to build ceramics by hand and to shun the traditional symmetry of the potter’s wheel marked a pivotal point in the evolution of modern studio pottery, and her monumental scale equaled the grandeur of her artistic vision.

Throughout her life, her artistic output was limited by lingering effects of brucellosis, which she contracted on her farm from drinking unpasteurized goat’s milk. Unfortunately, she struggled with lethargy and vision problems for the rest of her life.

McVey’s art was the subject of two major solo exhibitions, one at the Albert Knox Gallery in Buffalo in 1962, and the other at the Cleveland Art Institute in 1965. Her work is also in a number of collections today, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

|

||